Story in English

Andrei Geraschenko is a member of the writers’ unions of Russia and Belarus, and is the author of more than 20 books, including children’s books and books about the war.

Little Squirrel is written in memory of the children, women and the elderly who were killed in lands occupied by the Nazis (more often called the ‘Fascists’ by Belarusians) during the Second World War. In the story, the little squirrel is a soft toy that the Belarusian boy clutches in his hands, whose symbolism could have saved the boy from death. But this is not how the story ends. The lump in the reader’s throat, and the image of the toy squirrel laying in the bloodied snow, will remain long after the last page has been turned.

Andrei Geraschenko

LITTLE SQUIRREL

A story

Written in memory of every child who died in the Second World War

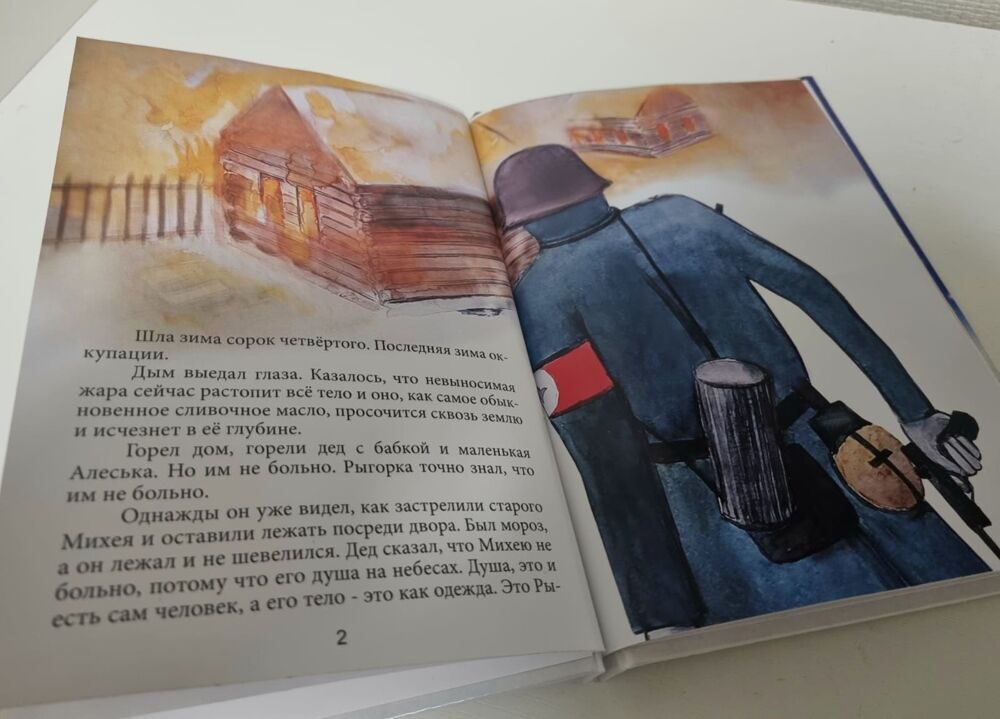

The smoke was gnawing at their eyes. It felt as if the unbearable heat would take their bodies any second, and melt them into the ground, like a block of butter.

The house was on fire. His grandpa and grandma and sister Aleska were on fire. But they weren’t in any pain. Ryhorka knew that they weren’t in any pain.

Once, he had watched as they shot old Mikhei, and left him in the middle of the yard. It was freezing, and he just lay there, not moving. Ryhorka’s grandpa had said that Mikhei wasn’t in any pain, because his soul was in heaven. The soul is the essence of a person, he said, and his body is like his clothes. Ryhorka knew this too. So his grandpa, grandma and Aleska weren’t hurting, because their souls were already in heaven. And Ryhorka was here. What would he do now, on his own?

The caustic smoke forced itself into his mouth and nose. He could barely breathe.

‘But what if my soul dies at the same time as my body? Will I never get to heaven?’ thought Ryhorka, scared. Rubbing the tears out of his eyes, he tugged away the old blanket that was covering the secret hatch.

His grandpa had known that the Germans could arrive any day, and showed him how to use the escape hatch. Ryhorka knew to listen very carefully, to check whether there was anyone on that side of the house, and then to climb out and run into the forest.

He felt a cold and surprisingly fresh breeze on his face.

Obersturmbannführer Neubert heard a strange noise. He looked at the ground and saw that lumps of snow were falling off the roof of the house. A trickle of bluish smoke was seeping out from a hole in one of the walls.

‘The wall could collapse – there must be a fire inside, if the snow is melting,’ thought the officer, stepping a few paces away from the house.

Suddenly there was another sound – somebody spluttering and gasping for breath. The hole at the bottom of the wall creaked, and a human hand poked out of it. Neubert took another step back, and slid an automatic pistol out of its holster.

Crouching close to the wall, he waited to see what would happen next. It would be foolish to call the other soldiers – he could frighten away the enemy who was about to show himself.

After the hand came a head, and then the rest of a dirty, ragged human figure.

‘Mein Gott, why is that man so small? Is he some kind of evil troll, crawling out of hell to punish me for my sins? Ah fuck, no, it’s just a little peasant boy. My nerves are shot! But how did he survive in there? We didn’t do it properly… we almost let him escape…’ Neubert muttered to himself, his pistol still raised in front of him.

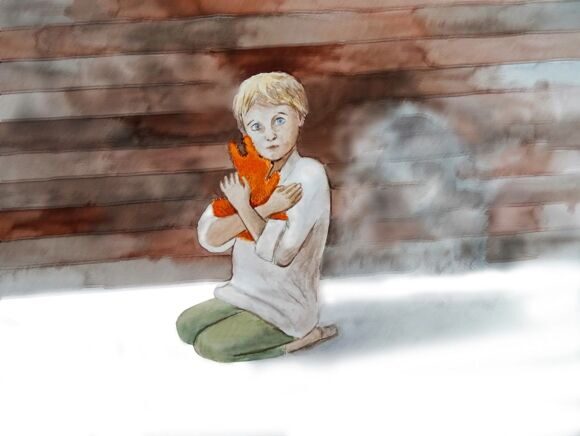

Brushing the snow off his threadbare toy squirrel, Ryhorka looked up, at a pistol pointing at his head ‒ and a tall German with his finger on the trigger.

He gave a quiet gasp, dropped the little squirrel, and tried to scurry back into the hatch.

Neubert lowered his gun, grabbed hold of Ryhorka by the collar, and held the boy, paralysed by fright, in front of him.

Ryhorka thought that his heart would burst through his chest, so heavily was it pounding. He felt fear in every cell in his body. He couldn’t move his legs and arms.

He had to run – run with all his might from the German. But the horror, like the terror a mouse feels when it runs into a snake, froze him to the spot.

‘Why didn’t I just kill him? I’ll shoot him – what good is he to me alive?’ thought Neubert, and reached his hand back towards the holster. But then he saw the soft toy squirrel, lying forlornly in the snow.

The squirrel made him think of Marta, and their own blonde child, Fritz.

One day he had arrived home from Munich with a soft toy squirrel for Fritz – a present for his Saint’s day.

Fritz was overwhelmed by the present, and wouldn’t put it down all evening.

‘What are you going to name it?’ Neubert asked his son. After thinking for a while, Fritz replied:

‘Little Squirrel. Just Little Squirrel...’

‘But you can’t just call him that. Everyone has to have their own name. You know that you are Fritz, and your Mutter is Marta. How about your little squirrel? He also needs a name…’

‘No, he can just be Little Squirrel!’ said Fritz stubbornly.

It was summer then. The hot and bright summer of 1943. Bavaria was bathed in green, and there, in the house where he had grown up, the war seemed like something far away, or not even real.

Ryhorka felt something wet and warm running down his legs. His panic had subsided, and he could move his body. Rubbing his tears into his cheeks, he threw his arms around Neubert’s boots, and cried quietly:

‘Mr F-Fascist, Mr F-Fascist, please don’t kill me! I’ll be your helper… I…’

‘Fuck, if you washed him this Russian boy would look just like Fritz. The same blue eyes, the same blonde curls. What is he yelping about? He’s probably begging me not to kill him. He’s clever… Fritz was clever too. I mean he is clever.’ Neubert lifted Ryhorka up and stood him in front of him again.

Picking the toy up from the snow, the lieutenant colonel stared at it, and, grabbing Ryhorka by the shoulder, asked:

‘Ist das dein Freund?’

Ryhorka looked at Neubert timidly. He couldn’t understand why the stranger with the gun was interested in his squirrel.

‘Wie heißt er?’ Neubert asked.

Ryhorka didn’t make a sound, and nervously hopped from one leg to the other. Neubert hadn’t noticed until then that his feet were bare.

‘What can I do with him?’ the German thought in anguish, staring back at the child.

‘Is he going to kill me or not?’ thought the boy, looking Neubert in the eyes.

In the last few months Neubert had come to think more about the spiritual world. He had become superstitious; he saw blood more often than he saw water, and he had spilled enough of that blood himself.

‘God, and what if these bastards come to Bavaria? What if they burn down my house with Marta and Fritz inside? Oh my God, he looks so much like Fritz! I will let him go. He can run into the forest. If he makes it then Fritz will live. But what then? He will die anyway – he won’t last long in the snow with bare feet. But those Russians are as tough as they come… Maybe he won’t die and the partisans will find him. Then that will be his fate. Let him run for now.’ Sweat formed on Neubert’s brow at the obsessive thought that his son’s life depended on whether this Russian boy could run as far as the forest.

‘He does look like Fritz,’ thought the German, and handed the little squirrel back to Ryhorka. The boy’s hands, shaking from the cold, clasped the soft toy to his chest as he looked up at the tall man.

‘Partisanen! Schnell, schnell! Biiistro!’ shouted Neubert. He turned Ryhorka towards the forest in the distance and gave him a gentle kick.

Ryhorka burst into tears again and refused to run.

‘He must be scared that I’m going to shoot him,’ thought Neubert. Smiling now, he demonstratively put his pistol on the ground:

‘No shoot! Partisanen – biiistro!’

This time Ryhorka ran. The biting snow turned his legs purple, but he blocked out the pain. He only had one thing in his mind – reaching the forest as quickly as possible.

He didn’t know what he was going to do next. All he knew was that he had to save himself from these strange-looking and strange-sounding fascist people, who had killed his family and burned his house down.

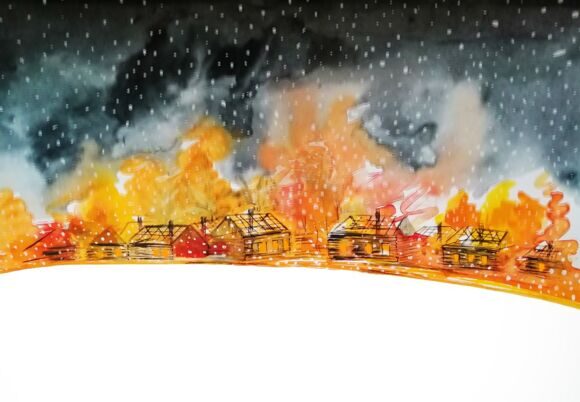

A gun fired mercilessly at him, one round after another. Ryhorka jumped to the ground, but when he got up to run again, another set of bullets knocked him off his feet. Paul chuckled at the sight of it, and kept shooting at the helpless little body lying in the snow.

Neubert ran up to Paul and struck him in the face with his fist. His eyes were burning with anger. ‘What are you doing, you idiot? This means that the Russians are going to kill my son!’

‘What was that for?’ Paul shouted, as he dropped his gun to massage his cheek.

Neubert knew that he had to explain what he had done. ‘You piece of shit, I almost saved that Russian! He could have got away!’

‘But I killed him!’

‘Count yourself lucky,’ said Neubert, coldly. He took a final look at Ryhorka’s lifeless body, barely visible in the distance.

At that moment the flames burst through the roof, and the house collapsed violently, a bonfire against the darkening sky.

Back in the car, the old corporal Scheinbach said, ‘They say the Russians are celebrating Christmas today...’ ‘Christmas? Good – I hope they enjoy the candles we left them!’ Paul laughed, waving at the village behind them, now smothered in flames. ‘But the Russians could come to Bavaria… They could get to Fritz and Marta… If they do, they will pay for it!’ replied Neubert, scowling out of the window at the snow-covered fields. There was only one thing he wanted now: to kill and to destroy, to destroy and to kill, so that rivers of blood washed away the memory of the Russian boy that Paul had killed. It was 1944.

***

Ryhorka came to from the agonising cold and sickening pain. He tried to get to his feet, but he couldn’t – he had two rounds of bullets in his legs.

The snow around his body was soaked with his blood, but night had fallen, and Ryhorka could only see a black puddle. He didn’t cry – gradually he stopped feeling the cold, and with every minute he became more numb to the pain.

Reaching his fingers out to the little toy squirrel lying next to him, he clutched it to his chest, and looked up at the sky. The stars were shining brightly. Ryhorka looked into his friend’s black button eyes, and whispered to it his secret:

‘My soul didn’t die, so I can go to heaven. That’s what Grandpa said. And you, you can come too. We will see Grandpa, Grandma and Aleska soon. It will be warm there, and nice, and all the fascists will be in hell. That’s what Grandpa sa‒‒’

Ryhorka closed his eyes, because he really wanted to sleep.

Heavy white flakes of snow fell on top of Ryhorka. They didn’t melt, and about two hours later the boy was covered in a soft, white shroud.

It was as if nature herself was horrified by what she had seen, and, powerless to change anything, she wanted to hide the travesty.

It was the winter of 1944. The last winter of the occupation.

Story in English

Я профессионально занимаюсь фотографией вот уже более 7 лет. В моем портфолио Вы сможете найти фотографии с более чем 100 отснятых свадеб.

Фотография для меня не только работа и уж никак не хобби. Фотография для меня - искусство и самое важное и ключевое занятие в жизни, а потому я подхожу к своей работе с максимальной ответственностью, в то же время оставляя пространство для творчества и креативных идей.

Если кто-то думает, что фотографии - это всегда скучно, однообразно и одинаково, спешу Вас переубедить. За свой многолетний опыт я не отсняла ни одной свадьбы, похожей на другую. Каждая свадьба уникальна и для каждого события мы совместно с клиентами подбираем сюжет, антураж, стиль и прочие нюансы съемки и обработки. Потому, если Вы решите обратиться за услугами ко мне, можете быть уверены, что Ваши фотографии не будут похожи на чьи-то чужие, будут по-настоящему оригинальными и качественными.

К слову о качестве: я работаю с первоклассной фототехникой, работаю профессионально, владею и использую в своей работе различные графические редакторы, учитываю все пожелания клиентов. Можете не сомневаться в том, что полученные кадры порадуют Вас и украсят семейный альбом.

Итак, если Вы ищете фотографа, не важно - будь то съемка церемонии бракосочетания или тематическая фотосессия, съемка в студии или на открытом воздухе, подготовка полноценного фотоотчета с мероприятия или же небольшая часовая съемка - просто свяжитесь со мной.

Любые пожелания, интересные идеи, замыслы, образы - я готова воплотить в кадре!